KEEP A WRITING BOOK

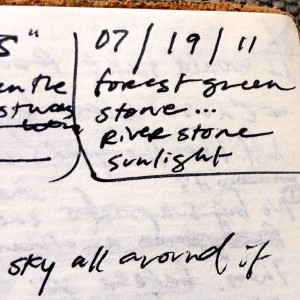

- Keep a writing journal where you deposit all of your written scraps. Whether it’s a single compelling word, a one-liner or an alternate version of something bigger, write it all down in one place.

- Even if random inspiration causes you to jot something on a napkin or a sticky note, store it within the pages of this journal, so that your entire writing arsenal is in one solitary location.

- Re-visit your book several times a year and enjoy the delayed inspiration.

EXAMPLE: Many times I’ve scribbled a phrase that seemingly made no sense when it was written; however, later, within the new context of my life, it made all the sense in the world. Whistle Stop, for example, was simply an intriguing phrase I entered into my journal … and it was a full year before it ever made sense.

When I first heard those words, I tried and tried to write a “Whistle Stop” song, but nothing in my vault of life experiences would support the theme. However, a year later, when I stumbled upon that phrase in my journal, my brain immediately snapped into focus because of a current circumstance. My great friend had recently lost his mother. Even though “Whistle Stop” meant nothing to me a year prior, in that moment it screamed “life is a train … and since you never know when the next whistle stop might be, in the meantime, don’t whisper softly the things that you want loudly to be.” This delayed inspiration was a result of keeping a journal and re-visiting it often with a fresh perspective.

IF STRUGGLING FOR IDEAS

Gather Information. Find a word or an idea (aka “Whistle Stop”) and collect every morsel of information that could possibly support it. Collect nouns/adjectives, read research papers, use Wikipedia, interview knowledgeable people, etc.

Grind & Explore. Take all of this raw information gathered and simply grind it into the ground. Stretch it, twist it, attempt to connect all dots while exploring all possible combinations. In this incubation period, it’s not about the major break through — the goal is to leave no stone unturned as you become overly acquainted with the subject.

Move On. It’s hard to do at times, but step three suggests you simply walk away from the muddled train wreck of thoughts in your head. Wash your hands of it. Move on to the next project. The reasoning here is that once all information has been collected and whittled to a nub, even though you’ve walked away from it consciencely, your sub-conscience has not forgotten about the task. While your conscience is away, your sub-conscience will play!

Revisit with New Perspective. Once you’ve survived the word jumble of the above steps and then departed for a time, come back to revisit the materials with a fresh head. Your sub-conscience has been connecting dots all the while — you will find the ideas have matured and your words will fall with much greater precision. NOTE: Even though I claim to have rarely written a song in one sitting, this process is the caveat. I have certainly schemed and schemed, walked away for a few months, then returned to write the final song all at once.

IF YOU ALREADY HAVE AN IDEA

If you’re lucky enough to already have a thesis, theme or idea, these very basic exercises will help you help them realize their full potential.

Establish a Color Palette. The art of visual communications suggests that colors elicit emotion as much as the words themselves. That said, I firstly apply a 3-color palette to each song and write within the rails of that mood, always mindful of the tonal subtleties (brick red is a very different feeling than salmon). Simply put, if your song is sunshine yellow, stem green and sky blue, you won’t be writing any purple lines — lavender, maybe, but not plum. This keeps your word choice as true to the core as can be.

Collect Nouns / Adjectives. When you have a seed idea, much like step one above, collect and absorb a number of tasty nouns and adjectives that support the theme. Yes, your hook needs to be potent but the supporting cast of words should have substantial character of their own.

Don’t Be Afraid of Research. If you’re serious about writing, know your subject well and never be afraid to learn more. Whether it’s a book, Google, Wikipedia or an old school personal interview, read about your topic and ask questions to gain context. You’ll often find some fruitful leads that will help you better map your song and navigate its nuances.

LITTLE THINGS WORK IN BIG WAYS

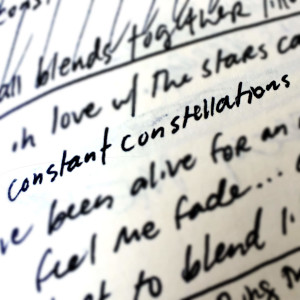

Alliterations. To revisit your 7th grade Lit class, an alliteration is the repeating of a consonant in succession (crystal clear, mad max, big boy, etc). When used within lyric, it can be a subtle moment with big impact.

The Magic C/K. Studies show that the hard C/K (cat, cup, kill, etc) is the most appealing sound to the human ear. It makes things memorable. As an example, I use the term constant constellations in my song Welcome the Change, in an attempt to double-dip on the lessons above.

Using Proper Nouns. Using proper nouns within your writing can be a very powerful tool, but it can also work against you. Choose wisely. Naming a specific town or lover’s first name has the ability to be extremely intriguing (drawing an audience into your story because it’s a vicarious experience); however, when used at the wrong moment, it can also alienate. The joy of song is that it’s universal — each person can interpret as they please and custom tailor the message to meet their wants. If an intimate love song is all at once interrupted by the mention of a specific name, there’s risk that the listener might immediately detach themselves from the overall sentiment because they simply can’t relate to the specific name.

Internal Rhyming. Rather than the more common rhyming of two end-phrases on two separate lines, this is a fine kind of rhyme that tries to align sublime rhymes inside a single line, two or more times — see what I did there? Internal rhyming. Like an alliteration, when used in succession, this rhythmic mechanism can be quite catchy.

CHALLENGES

Your First Line. Contrary to popular belief, the most important moment in a song is not the hook, it’s the first line. Because it’s your opportunity to either snare the listener or invite them to press next, this line cannot be ordinary. If it comes across as cliche, it gives the listener no incentive to stick around because they’ve heard it before. NOTE: I always try to make my first line sound like it should be the third line — a more progressed piece of the story.

Scrap Silver to Make Gold. Though you may be in love with one of your verses, there are times when it simply doesn’t fit the scope of the collective song and it must be abandoned. Yes, it may be a stellar individual verse but when you look at the big picture, is The Song more or less cohesive as a result? If the answer is less cohesive, then scrap it and go for gold. NOTE: keep that verse in your journal, it can always be repurposed in another song down the line — somewhere where it will shine brighter because it belongs.

Second Verse, Not Second Best. Once you’ve spent a verse and introduced your chorus, your second verse can act as the nail in the coffin. They’re listening, they’re intrigued; this is the moment they’ll decide to be repeat listeners or not. Take it to the next level. When advancing into your second verse, always keep in mind, what’s new, what’s next? If your second verse is more of the same, think bigger. Be more aggressive. Use an alliteration.

Are Bridges Necessary? No. More formulaic pop songs tend to utilize bridges as a way to break up monotony. If your song is monotonous, I encourage you to write a bridge to give the listener a reward for their hard work and dedication; however, if your song is filled with musical rewards, unique lyric, refreshing metaphors and hooks, a bridge is not a mandatory ingredient.

Ask Yourself: Has it been said before? If so, how can I say it differently? It’s okay to say basic things in very human ways without self-servingly speaking over the heads of your listeners, but with the wash of music that exists in this world, there is little room for redundancy. Say timeless things that have been said before but always challenge yourself to say them in one-of-a-kind ways.

LISTEN BEFORE IT’S WRITTEN

Most of my songs start music first, with a chord progression on the guitar or piano, then I retrofit words to fill the spaces. My lyrical tool box is much more robust than my musicianship, therefore, to me, fitting words into music is much easier than the alternative.

It may sound odd, but once I have my chord progression established, I sit with my guitar and endlessly play through the structure, filling the air with ad lib, mumbles, oooohs, aaaaahs, random lyric and whatever else decides to come out. No pen. No paper. I find that keeping an open mind and simply letting the sounds flow can be VERY telling.

Eventually, you’ll find a pattern.

You’ll find that certain vowels keep poking up in the same place each time. You’ll find certain lines beginning with the same alliteration each time. No matter how random you try to be, you’ll find that amongst the chaos, there are constants. Be a Song Whisperer — embrace those constants and listen to them as if it’s the song revealing itself to you, piece by piece.

After adequately making a fool of myself and noting the revelations, I plot out the constants in a sort of road map. Once you know your anchor points, back-filling the rest of the content is suddenly less random. If I know my second line wants to end with an “eeee” sound and the third line wants to start with a “B” alliteration, rather than pulling random thoughts from the air, the thought process is now: “What line can I think of that ends with an “eeee” rhyme scheme, while also introducing my “B” alliteration?”

This step takes some confidence; however, I guarantee if you open your mind and let the unwritten song flow through you, you’ll find that it speaks to you, ultimately revealing little pieces of itself. By listening to the promptings, your song will assume a more natural feel because nothing was forced or contrived — on the contrary, it was meant to be.

Leave a Comment